Laparoscopic Incisional Hernia Repair

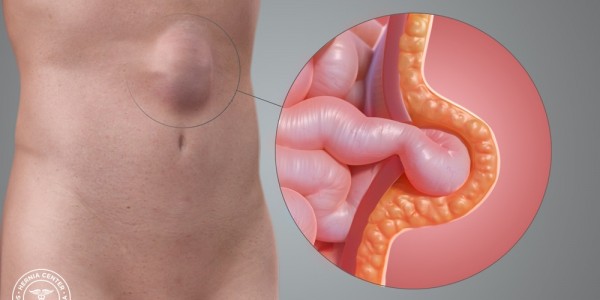

A hernia is the protrusion of tissue or part of an organ through the bone, muscular tissue, or the membrane by which it is normally contained. Hernias can be classified as internal or external and as abdominal or thoracic.

Abdominal wall hernias can occur spontaneously (presumably from congenital defects) or after surgery. When they occur after surgery, they are called incisional hernias, which can range from small defects to extremely large ones. Some defects are so large that contents are irreducible owing to an abdominal wall that is chronically injured and reduced. This is referred to as “loss of domain."

Incisional hernias are very common. They are the second most common type of hernia after inguinal hernias. Approximately 4 million laparotomies are performed in the United States annually, 2-30% of them resulting in incisional hernia. Between 100,000 and 150,000 ventral incisional hernia repairs are performed annually in the United States.

Incisional hernias after laparotomy are mostly related to failure of the fascia to heal and involve technical and biological factors. Approximately 50% of all incisional hernias develop or present within the first 2 years following surgery, and 74% occur within 3 years.

Depending on size, the repair of an incisional hernia varies from simple suturing to major reconstruction of the abdominal wall with creation of muscle flaps and the use of large pieces of mesh. This can be done with an open approach or laparoscopy.

In 1993, LeBlanc reported the first case of laparoscopic incisional hernia repair with the use of synthetic mesh. [7] The procedure involves the placement of a mesh inside the abdomen without abdominal wall reconstruction. The mesh is fixed with sutures, staples, or tacks. The recurrence rate of laparoscopic repair is reported as equal to or less than that of open repair. Incisional hernia repair is considered a challenging procedure, especially with recurrent hernias, in which the chances of failure increase with each surgical attempt.

Risk factors for hernia formationA 0.1% rate of acute laparotomy wound failure has been reported in the literature.[10] The true rate of laparotomy failure is about 11%; of these patients, 94% present with recurrence in the first 3 years after the operation. [3] The real laparotomy wound failure rate is therefore 100 times greater than previously thought. The early mechanical failure, therefore, occurs early in the course of the disease, and the healing skin conceals a myofascial defect that enlarges or appears later.

Perioperative shock is a recognized risk factor for incisional hernia formation.

Upper midline incisions have a higher incidence of hernia formation than other types of incision do.

Technique is a factor as well. The configuration of the collagen bundles of the abdominal wall are oriented transversely; therefore, a transverse suture line is mechanically more stable, as it encircles the fibers rather than splitting them.

Indications

The hernia may be asymptomatic, but usually, it is easily palpated and the defect can be delineated. In obese patients, the authors recommend computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen with contrast to better outline the anatomy.

Indications for performing a hernia repair are as follows:

-

Symptoms such as pain and abdominal enlargement

-

Risk of incarceration, especially hernia sacs with a small neck that contain bowel

-

Suitable size - The best candidates are small to moderate-sized hernias in which the contents can be easily reduced and port-site hernias

Laparoscopic incisional repair compares favorably with open repair in terms of shorter operating time, reduced length of stay, and lower costs. [15]

Contraindications

Patients with major comorbidities, such as congestive heart failure (CHF) or severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), may be at a higher risk of complications when undergoing general anesthesia and may not benefit from hernia repair, especially if mild symptoms are the indication. Risks and benefits must be evaluated on an individual basis.

Contraindications for laparoscopic ventral hernia repair are the same as those for any major laparoscopic operation and include the following:

-

Inability to create a working space

-

Acute or emergency procedure (ie, bowel obstruction)

-

Prior multiple surgeries with open repair and mesh placement

-

Infection of skin or surrounding structures overlying the repair (all infection must be treated and cured before the procedure)

-

Ascites with Child class C cirrhosis

Obesity is not considered a contraindication, though obese patients should be counseled regarding the increased risk for hernia recurrence. Therefore, prior to the hernia repair, a bariatric evaluation is recommended. Patients are encouraged to lose weight preoperatively, if possible.

Hernias away from the midline can represent difficult cases and may be more amenable to open repair. This happens especially when bone fixation will be required—as, for example, with posterolateral hernias close to the flank and lumbar areas and with very high or low hernias in which the ribs, pubis, or xiphoid process may be used to fixed the mesh.

Technical Considerations

The abdominal wall is situated between the xiphoid process cephalad and the pubic bone caudally. Laterally, it extends from one side of the lumbar spine circumferentially to the other side, having the rib cage and the iliac crest as limits.

The structures or different components of the abdominal wall include, medially, the rectus abdominis and, laterally, the external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis and their respective fascias. These structures provide the support that maintains the integrity and limits of the abdominal cavity. The muscular and aponeurotic layers are covered by subcutaneous tissue and the skin. These last two structures have no specific role in the pathophysiology of incisional hernia.

Although obesity is related to an increase in subcutaneous fat, it is the increased intra-abdominal pressure that overcomes the firm containment of the muscular and aponeurotic components and places obese patients at risk for incisional hernias.

For surgeons, the anterior abdominal wall is of special interest regarding incisional hernias. The following discussion focuses mainly on this structure.

The multiple components that make up the anterior abdominal wall, from outside to inside, are as follows:

-

Skin

-

Subcutaneous tissue (Camper and Scarpa fascias)

-

Anterior aponeurosis

-

Muscle (rectus abdominis, external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis)

-

Posterior aponeurosis

-

Transversalis fascia

-

Peritoneum

Already identified weakened areas are prone to incisional hernias. These present a change in the configuration of the layers and include the following:

-

Midline - The center of the abdominal rectus has the joining of the anterior and posterior aponeuroses of the rectus abdominis; most incisions are created in the midline, usually for exploratory laparotomies in order to gain better exposure of the abdominal cavity; the midline also has the highest amount of pressure, which makes it prone to incisional hernia

-

Arcuate line - The posterior aponeurotic sheath of the rectus abdominis becomes anterior two fingerbreadths below the umbilicus

-

Semilunaris line - This extends laterally along the edges of the abdominal rectus; it is the joining of the rectus and the internal oblique and transversus abdominis aponeuroses

The difference between the open and laparoscopic approaches consists of the access to and exposure of the defect. In the open procedure, the abdominal wall is incised over the defect. The disruption of surrounding tissue can lead to devascularization. When large incisions are employed, a higher incidence of seromas, hematomas, and wound infections has been reported.

Although technically challenging, laparoscopy can be used to evaluate other defects or even synchronous inguinal hernias. However, the laparoscopic approach has been criticized for not resecting the hernia sac and not restoring the anatomy, thereby allowing the persistence of abdominal bulging and an abdominal wall that is mechanically unstable and has uncoordinated muscles. In addition, placement of a mesh over the defect leads to seroma formation in a large number of patients.

Complication preventionSeromas may be caused when a hernia sac is left. The use of abdominal binders may prevent their development. Some authors cauterize the hernia sac or even dissect it, but this is technically challenging.

The authors do not routinely place drains.

To prevent enterotomies, take extreme caution when using energy devices inside the abdomen. Dissection must be with blunt technique as much as possible. Careful identification of the structures and inspection of the abdominal cavity for intestinal injuries must be done if these are suspected. The major problem with enterotomies is failure to recognize them intraoperatively.

To minimize the risk of hemorrhage, antiplatelet drugs and warfarin should be stopped preoperatively. Inability to withhold these drugs should be considered a strong contraindication to elective hernia repair. Careful hemostasis should be achieved. In some patients, prophylactic anticoagulation may be delayed in order to decrease postoperative bleeding.

Smoking places patients at an increased risk of wound infection and, therefore, of incisional hernia. Patients should be counseled about the importance of quitting smoking for at least 2 weeks (preferably, 8 weeks) perioperatively.

A meta-analysis of 880 patients who underwent laparoscopic versus open primary repair showed benefits of the laparoscopic approach, such as decreased wound infections, hospital stay, hematomas, and pain. Laparoscopic repair has the disadvantage of increasing the risk of enterotomies. [16]

In an incarcerated hernia, dissection of the sac contents may be easier with the open approach. With laparoscopy, it is difficult to estimate the amount of bowel or omentum involved, especially when dense adhesions are present.

Other authors have described the same advantages and properties of the laparoscopic approach as compared with the open approach.

The conversion rate of these procedures is an impressive 2.4%, with an enterotomy rate of 1.8%, confirming the low risk of this technique. The recurrence rate of 4.2% is low and underscores the effectiveness of the laparoscopic approach. This procedure may become the standard of care in the near future.

The practicability of laparoscopic incisional hernia repair is evidence-based, with large series of patients and high-quality long-term follow-up.

In a systematic review and meta-analysis of of randomized controlled trials comparing laparoscopic with open incisional hernia repair, Al Chalabi et al concluded that the short- and long-term outcomes of the two approaches (with particular regard to hernia recurrence) were highly comparable.